|

Hannah's Second Marriage Hannah's Second Marriage

Not long after Henry's death on August 9, 1693 in East Greenwich it was recorded that Charles Hazelton had taken Hannah Matteson as his wife. Hannah being married wearing only her shift and no other clothing.

Following old English common law a man marrying a widow would be responsible for any debts of the previous husband if the bride brought any of his property with her. By being married only in her shift Hannah was making it known that she was bringing none of Henry's property into this new marriage and her new husband should not be held liable for any oif her previous husband's debts.

Land evidence shows that on July 29, 1693. just one week prior to her marriage with Charles Hazelton, Hannah had sold to George Vaughn the 10 acres of land that Henry had bought from John Knight.

Little is known of what became of Hannah and her new husband. We have yet to find a record of their deaths in either East or West Greenwich which suggests that at some later date they may have moved elsewhere.

|

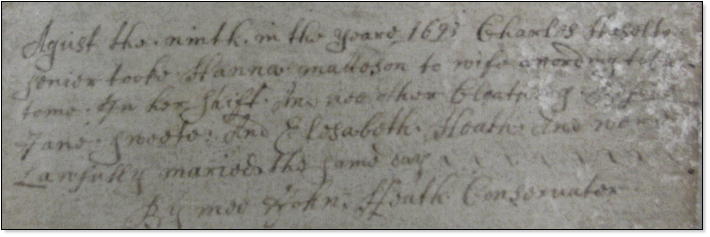

August the ninth in the year 1693 Charles Hazelton

senior took Hanna Matteson to wife according to

custom in her shift and noe other cloathing before

Jane Sweete and Elizabeth Heath and were

lawfully married the same day.

By mee John Heath conservator |

Smock/Shift Weddings

From: Old-Time Marriage Customs in New England.

Journal of American Folklore 6 (April-June 1893)

By Alice Morris Earle

The most eccentric marriage custom that I have noted in America is what has been termed a “smock marriage,” or “marriage in a shift.” It was believed in this country, and in Old England (and I have heard that the notion still prevails in parts of England to this day), that if a widow should wear no garment but a shift at the celebration of her second marriage, her new husband would escape liability for any debt previously contracted by her or by her former husband. Mr. William C. Prime, in his delightful book, “Along New England Roads,” page 25 et seq., gives an account of such a marriage in Newfane, Vermont. In February, 1789, Major Moses Joy married widow Hannah Ward; the bride stood with no clothing on within a closet, and held out her hand to the major through a diamond-shaped hole in the door, and the ceremony was thus performed. She then appeared resplendent in brave wedding attire, which the gallant major had previously deposited in the closet for her assumption. Mr. Prime tells also of a marriage in which the bride, entirely unclad, left her room by a window by night, and, standing on the top round of a high ladder, donned her wedding garments, and thus put off the obligations of the old life. In some cases the marriage was performed on the public highway. In Hall’s “History of Eastern Vermont,” page 587, we read of a marriage in Westminster, Vermont, in which the widow Lovejoy, while nude and hidden in a chimney recess behind a curtain, wedded Asa Averill. “Smock marriages” are recorded in York, Maine, in 1774, as shown on page 419 et seq. of “History of Wells and Kennebunkport.” It is said that in one case the pitying minister threw his coat over the shivering bride, one widow Mary Bradley, who in February, clad only in a shift, met the bridegroom on the highway, half way from her home to his.

The traveller Kalm, writing in 1748, says that one Pennsylvania bridegroom saved appearances by meeting the scantily-clad widow-bride half way from her house to his, and announcing formally, in the presence of witnesses, that the wedding clothes which he then put on her were only lent to her for the occasion. This is curiously suggestive of the marriage investiture of eastern Hindostan.

In Westerly, Rhode Island, other smock marriages are recorded, showing that the belief in this vulgar error was universal. The most curious variation of this custom is given on page 224, vol. ii. of the “Life of Gustavus Vassa,” wherein that traveller records that he saw a shift marriage take place on a gallows in New York in 1784. A malefactor, condemned to death and about to undergo his execution, was reprieved and liberated through his marriage to a woman thus scantily clad. This traveller’s yarn deserves not, of course, the credence accorded to the previously stated authentic records.

From: The Smock Wedding: Part Nude Matrimony, Part Public Bankruptcy Proceeding

By Timothy Sexton

http://www.associatedcontent.com/article/1088318/the_smock_wedding_part_nude_matrimony.html?cat=41

The smock wedding was conducted most often amongst early settlers of New England as a remnant of English common law. In a smock wedding the bride and the bride alone is attired in only her underwear, a smock or, occasionally, even less. The reason for this unusual and probably quite surprising choice had to do with English common law which stated that any man who married a widow became responsible for any debts of the bride's most recent husband if she brought any of her deceased husband's property with her. The core problem here was that women were not allowed to own anything, therefore even her own clothing would be considered their deceased husband's property. Even if the woman herself made the clothing, which was usually the case, then bringing that clothing into the new marriage automatically made the new husband responsible for all the debt incurred by the dead husband.

Return to Facts and Findings Return to Facts and Findings

|